Is Big Tech becoming more cutthroat?

👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a subscriber-only issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. If you’ve been forwarded this email, you can subscribe here. Is Big Tech becoming more cutthroat?Is it the end of a golden age of Big Tech, when jobs at leading companies offered high-impact work, top compensation, and good work-life balance? More signs suggest harsh perf management is the normA few years ago, companies like Google, Microsoft and Facebook were known as places where – inside certain organizations – some engineers could earn large sums of money for doing comparatively little work, and wile away the work week waiting for their large new joiner equity to vest over four years. This chill approach is what the “rest” in rest-and-vest refers to, which was a popular phrase at the time for it. These places also had many teams where work was laid back, and it was possible to “coast” and get by doing relatively little. In 2017, Business Insider interviewed several such folks and wrote:

A culture of lenient performance management at the biggest tech businesses contributed to laidback work patterns; I talked with managers at the likes of Google and Microsoft at the time who were frustrated that the system made it hard to manage out folks who were visibly checked out, and were hard to motivate to do even the bare minimum work. Fast forward to today, and there are signs that Big Tech employers are being tougher than ever in performance management, and any tolerance of “rest and vest” culture is history. This article covers:

Related to this article is our two-part deepdive into How performance calibrations are done at tech companies. 1. Meta: first performance-based mass layoffsMeta did no mass layoffs for its first 18 years of its existence, until November 2022 when it let go 13% of staff. Back then, there were business reasons. I wrote at the time:

Six months later in early 2023, the company reduced headcount by another 11%, letting go 10,000 people The reasoning was that it had overhired during the pandemic years of 2020-2021, and was too bloated. The layoffs flattened the organization and boosted efficiency. That was two years ago, and since then Meta has become more efficient: it generates more revenue ($164B per year) and profit ($62B) than ever before, and its value is at an all-time high of $1.8 trillion dollars. It’s in this context that Meta announces its first-ever performance-based mass layoffs. Five percent of staff are expected to be let go, starting this week with around 3,700 people. An internal email from Mark Zuckerberg explains why, as reported by CNBC:

This clarity that it’s “low performers” who are being fired, is new. The large mass layoffs of 2022-23 were justified differently. Of course, low performers are at risk of being let go in most circumstances. However, in Meta’s previous layoffs, plenty of high-performers were also cut who worked in teams seen as bloated cost centers, or targeted for sharp headcount drops. 2. Microsoft: performance-based firings are backMeta isn’t the only tech giant doing this; Microsoft is doing the same on an individual basis. Also from Business Insider:

One of several termination letters was reported by Business Insider. It reads:

Just to repeat, performance-related firing is commonplace, but what’s different here is how short and quick the process is. Previously, most of Big Tech followed a standard process for workers seen as in need of improvement:

But now, Microsoft seems to be skipping PIPs and also not offering severance in some cases. This is unusual, given how differently the tech giant had treated employees since Satya Nadella became CEO. It also feels unusually petty to cancel severance packages for those affected, especially as Microsoft is reporting record profits. Is it a message to low performers to expect nothing from the company? Microsoft getting “cutthroat” in its performance-management is also out of character, as it was Nadella who introduced a more lenient performance management approach, back in 2014. 3. Evolution of Microsoft’s performance managementBetween the 1990s and 2013, Microsoft used a stack ranking system for performance management, which wasn’t advertised to employees until the mid-2000s – although many knew about Microsoft’s “vitality curve” for ranking engineers and managers. Under this, workers high on the curve got outsized bonuses and pay rises, and those low down the curve; well, they got managed out. In 2004, Mini Microsoft (an anonymous employee at the company, blogging in the public) wrote a post explaining how the then still-secretive stack ranking worked:

From 2004 – mostly thanks to this blog post – stack ranking was no longer a secret, but it wasn’t until 2011 that then-CEO Stever Ballmer acknowledged its existence in an internal email, writing:

The buckets were pre-defined, supposedly as 20% (top performers), 20% (good performers), 40% (average), 13% (below average), and 7% (poor performers). I worked at Microsoft starting in 2012, the year after the existence of the stack ranking system became public knowledge. Knowing the distribution made me hope for a grade of 1-2, which would have meant my manager saw me as the “top 40%” within the team. I ended up getting a “3” in 2013, which I was disappointed with, as I interpreted it as being in the bottom 20th to 60th percentile. Later, I talked with a HR person, who told me that nobody at Microsoft was ever happy with their grades:

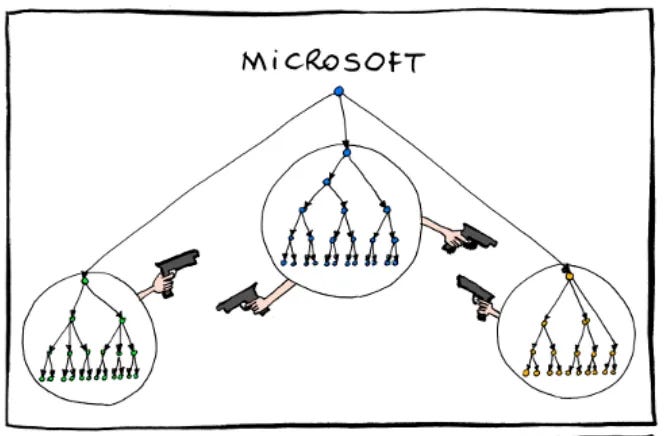

Stever Ballmer’s departure spelt the end of the stack ranking system. Shortly after Ballmer announced his retirement in August 2023, the company announced the system was also being retired, effective immediately in November 2023. There are a few possible reasons why Stack Ranking went extinct: 1. Office politics ruled Microsoft. From the mid-2000s, it was increasingly clear that internal politics was more important than building products customers loved. Microsoft was blindsided by the 2007 launch of the iPhone, and the launch of Android the next year. It took three more years to finally launch a competitive device – the Windows Phone in 2011. By then, iPhone and Android had captured the bulk of the smartphone market. In 2011, Google software engineer and cartoonist Manu Cornet drew a cartoon about how he perceived Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, and Oracle. This was what how he represented the Xbox maker:

This image went viral, even though Manu never intended it as a big joke in his comic strip, as he explains in The Man Behind the Tech Comics. The intended target of the joke was Oracle, but his image of Microsoft captured a widely perceived truth. Back then, there was close to zero collaboration between divisions at Microsoft, which were thousands of employees in size; like Windows Office, Server, Xbox, and Skype. I experienced the lack of collaboration – to the point of hostility – first-hand. In late 2013, my team was building Skype for Web, which we positioned as a competitor to Google Hangouts. We had a problem, though: in order to start a video or voice call, users needed to download a plugin which contained the required video codecs. We noticed Google Hangouts did the same on Internet Explorer and Firefox, but not on Chrome because the plugin was bundled with the browser for a frictionless experience. My team decided we had to offer the same frictionless experience on Microsoft’s latest browser, Edge, which was in development at the time. After weeks of back-and-forth, the team politely and firmly rejected bundling our plugin into the new Microsoft browser. The reason? Their KPI was to minimize the download size of the browser, and helping us would not help them reach that goal. It was a maddening experience. Microsoft could not compete with the likes of Google due to internal dysfunction like this; with teams and individuals focused on their own targets at the expense of the greater good for the company and users. 2. Stack ranking pinpointed as the core of the problem. In 2012, Vanity Fair published Microsoft’s lost decade, which said:

3. Investor and board pressure. By 2013, Microsoft’s stock had been flat for about 12 years. It was clear that cultural change was needed to turn business performance around, and removing the hated stack ranking system was one of the easiest ways for the leadership team to show that change was afoot. 4. Ballmer’s exit. Several leaders including Head of HR Lisa Brummel were never in favor of stack ranking, as Business Insider reported at the time. With Ballmer gone, executives could push decisions that would’ve previously been vetoed, before a new CEO took the helm. Satya Nadella replaced stack ranking with a more collaborative performance review system. As CEO, he recognized the cultural problems Microsoft had. In his 2017 book, Hit Refresh, he recalled the pre-2014 times:

A new performance review system attempted to address the problems, rating employees in three areas:

Microsoft also got rid of its vitality curve (the stack ranking system), starting from 2014. The changes resulted in a different performance review process, where individual impact carried less weight. In 2022, Microsoft even started to measure how many of its employees said they were “thriving”, which it defined as being “energized and empowered to do meaningful work.” Note that this was at the peak of the hottest job market in tech, when attrition spiked across the sector, and even Big Tech needed new ways to retain people. Signs that performance management was changing again were visible in 2023, when last September, Microsoft quietly introduced a new field for managers called “impact designators.” They had to rate the impact of their reports and not disclose this to employees. The ratings determined bonuses and pay rises. As a former engineering manager, what surprised me about this lowkey change was not that it happened, but rather that it raises the question of what Microsoft was doing before? “Impact designator” is another name for “multiplier”, used in most tech workplaces. Ahead of performance calibration meetings, managers often know this information and must fit the budget, or can sometimes exceed it. Multipliers are finalized in the calibration which helps for dividing bonus pots, equity refresh, and pay rise budgets. So it was a surprise to learn Microsoft operated without managers setting or recommending multipliers for nine years, as part of the performance process. 4. Even without stack ranking, there’s still bucketingThe demise of divisive stack ranking was cheered; but in reality, all larger companies still operate ranking frameworks today. At most mid-sized-and-above companies, performance review processes have the explicit goal to identify and reward top performers, and to find low performers and figure out what to do next. We cover the dynamics of the process in a two-part deepdive. Performance calibrations at tech companies, including:... Subscribe to The Pragmatic Engineer to unlock the rest.Become a paying subscriber of The Pragmatic Engineer to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content. A subscription gets you:

|

Comments

Post a Comment