How tech companies measure the impact of AI on software development

Hi – this is Gergely with the monthly, free issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of senior engineers and engineering leaders. If you’ve been forwarded this email, you can subscribe here. Many subscribers expense this newsletter to their learning and development budget. If you have such a budget, here’s an email you could send to your manager. If you’re not a full subscriber, you missed several deepdives and The Pulse issues. How tech companies measure the impact of AI on software developmentHow do GitHub, Google, Dropbox, Monzo, Atlassian, and 13 other companies know how well AI tools work for devs? A deepdive sharing exclusive details, with CTO Laura TachoAI coding tools are widespread across tech, with 85% of software engineers using them at work, according to our 2025 tooling survey. But things like tokens aren’t exactly cheap, and companies are spending more on AI tools. So, how do companies measure whether or not they are worth the money? To find out, I turned to Laura Tacho, CTO at DX, which helps companies to measure engineering efficiency. Longtime readers may remember Laura from three years ago, when she shared thoughts on measuring developer productivity and gave suggestions for how to get started in this tricky field, in her deepdive Measuring Developer Productivity. In this article, we cover:

Disclaimer: I am an investor in DX, of which Laura is CTO, but this article is not paid for by DX or sponsored in any way. In fact, I reached out to Laura about taking part. Read more in my ethics statement. Related deepdives on measuring developer productivity:

The bottom of this article could be cut off in some email clients. Read the full article uninterrupted, online. With that, it’s over to Laura. Open up LinkedIn, and it only takes about 30 seconds to stumble across a post about AI changing how companies develop software. There are headlines about companies, mostly US-based Big Tech, supposedly shipping huge amounts of AI-generated code – Google with 25%, Microsoft with 30% – with reports implying all this code lands in production, and some founders say AI can replace junior engineers. On the other hand, studies like the recent METR study about AI’s impact on open source software tasks, find that AI can mess with our time perception and actually slow us down, even when we think we’re moving faster. When it comes to showing AI impact, the headlines are pretty one-dimensional. AI can write a lot of code which saves time – or does not. Meanwhile, we’re careening toward the biggest pile of tech debt the world has ever seen. I’m often left wondering why our industry has become fixated on lines of code (LOC) again; why is this the metric in the headlines? What about quality, innovation, time-to-market, and reliability? We agreed a long time ago that LOC is a bad measure of developer productivity, but it’s easy to measure LOC, and in the absence of a clear alternative, easy to latch on to. It also makes for good headlines. Right now, many engineering leaders are making big decisions about AI tools without really knowing what works and what doesn’t. According to research in LeadDev’s 2025 AI Impact Report from 880 engineering leaders, 60% of leaders cited a lack of clear metrics as their biggest AI challenge. My own experience aligns with this. I have numerous conversations each week with leaders who are feeling pressure to deliver results like in the headlines, and are at the same time frustrated by boards or exec teams fixated on measuring LOC. There’s a gap between what leaders need to know and what’s being measured and talked about, and this measurement gap only widens as new tools and capabilities hit the market. Closing this measurement gap is my job. I’ve worked on dev tools for over a decade, and since 2021, I’ve been researching and advising companies on improving developer productivity. Since joining DX as CTO two years ago, I now do this on an even larger scale, working closely with hundreds of amazing companies in the complex and important space of developer experience, engineering efficiency, and AI impact. Earlier this year, I co-authored the AI Measurement Framework, which is a recommended set of metrics to track AI adoption and impact across engineering teams. This framework is built upon rigorous field research, as well as data analysis from 400+ companies, and how they’re actually rolling out and measuring AI tools. Today, we’ll look into how 18 tech companies measure AI impact in the real world, giving you a peek into the research that goes into something like the AI Measurement Framework. I’ll share:

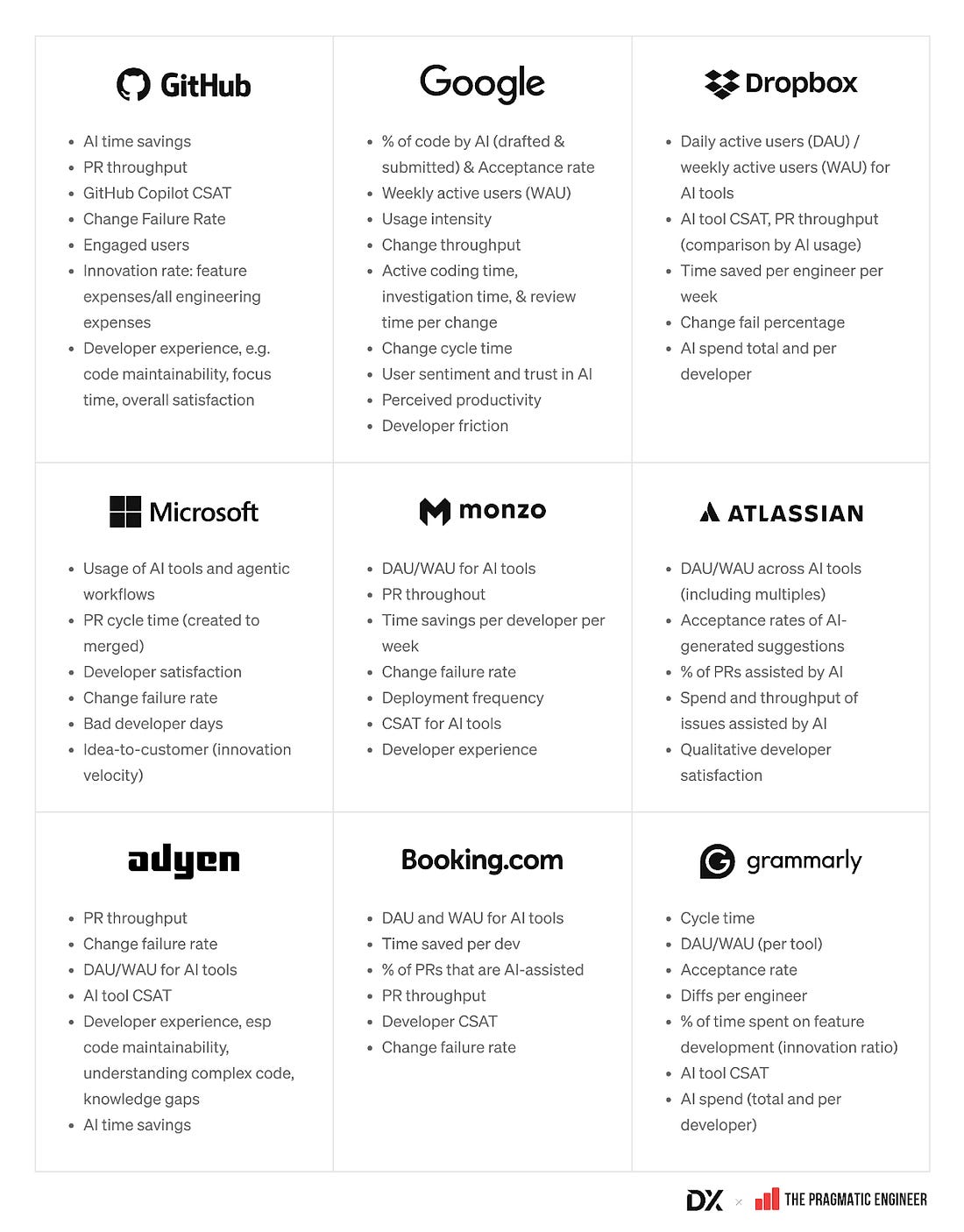

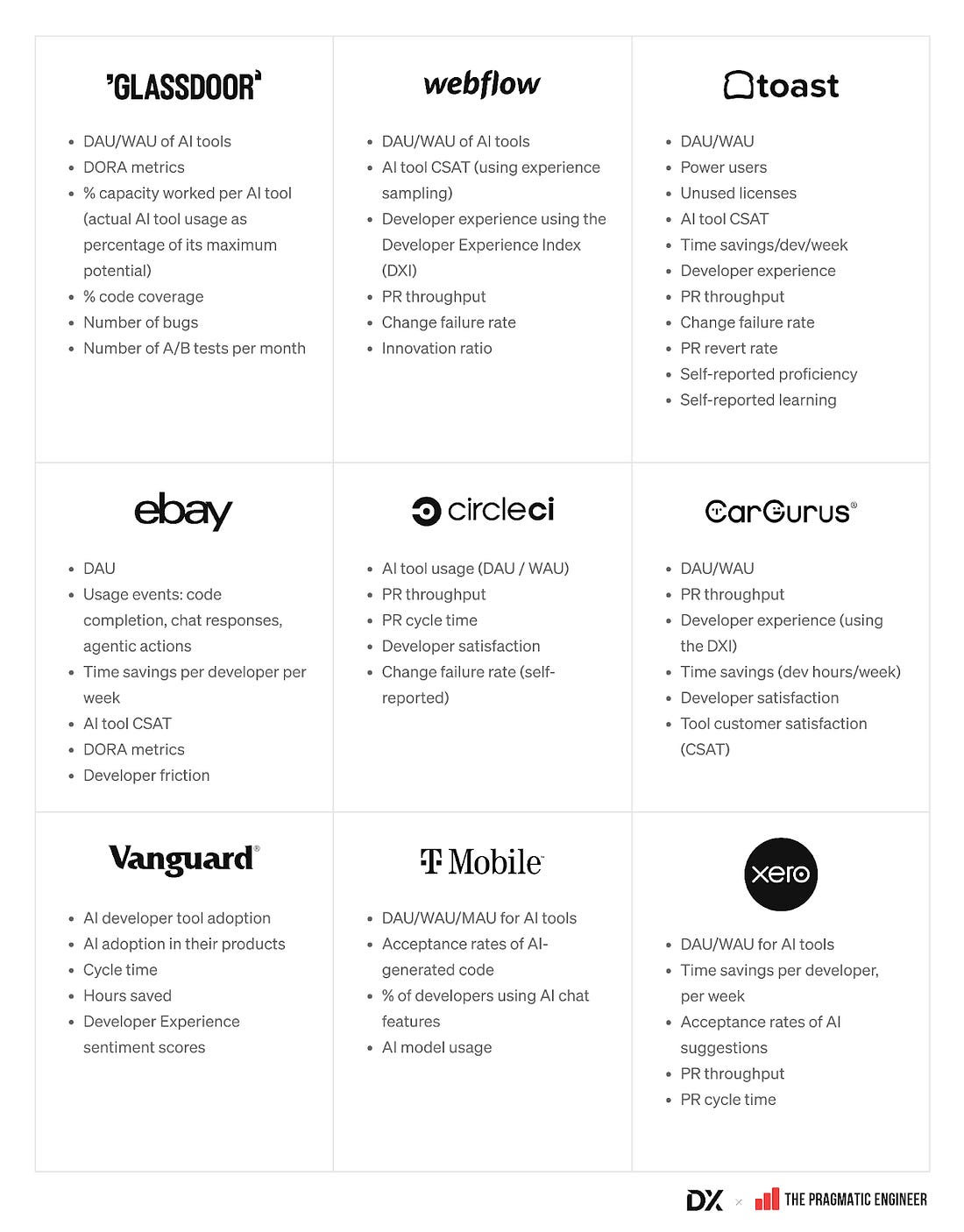

1. How 18 top companies measure AI impactFirst, an overview of real metrics which 18 companies use to measure the impact of AI on their work; including GitHub, Google, Dropbox, Microsoft, Monzo, Atlassian, Adyen, Booking.com, and Grammarly: There’s a lot we can learn from the similarities and differences in the approaches shared above. Let's break it down. 2. Solid foundations matter for measuring AI impactUsing AI to write code doesn’t change the mechanics of what makes good software good, or what matters to the business. Software still needs to be high quality, easy to maintain, and delivered at speed. That’s why you’ll notice that many of the metrics shared above look the same as in the pre-AI world, such as Change Failure Rate, PR Throughput, PR Cycle Time, and Developer Experience. You don’t need totally new metrics to measure AI impact. Instead, focus on what’s always mattered. Is AI helping your organization get better at those things? A hard truth is that organizations that can’t yet articulate “what matters” when it comes to engineering org performance and developer productivity, are finding it almost impossible to measure AI impact beyond surface-level metrics like LOC or acceptance rate. The 18 organizations above have already invested heavily in measuring developer productivity and developer experience, which puts them in a great position to more easily see the impact of AI tooling. While we shouldn’t start from scratch, we do need new, targeted metrics to see exactly what is happening with AI usage. Knowing where people use it, and to what extent, influences things like decisions about budgets, tool rollouts, and enablement, all the way to SRE and security, governance, and compliance. AI metrics can show:

Core engineering metrics show:

Take a look at metrics used by Dropbox, which is a good example of mixing existing metrics with new AI-specific ones. Dropbox has an adoption rate of 90% of engineers regularly (weekly+) using AI tools, which is really high compared to the industry average of closer to 50%. Dropbox didn’t get to this high level of adoption by relying on the curiosity and grit of individual developers. They took a structured, organizational approach that had good metrics built in from the start. On the AI side, Dropbox tracks these metrics:

These show who exactly is using AI, what their experience is, whether it’s actually saving them time, and how much it all costs. Then by layering in the Core 4 framework, which Dropbox uses to track core engineering metrics, they can see how AI adoption affects software delivery at a larger scale. Specifically, they look at:

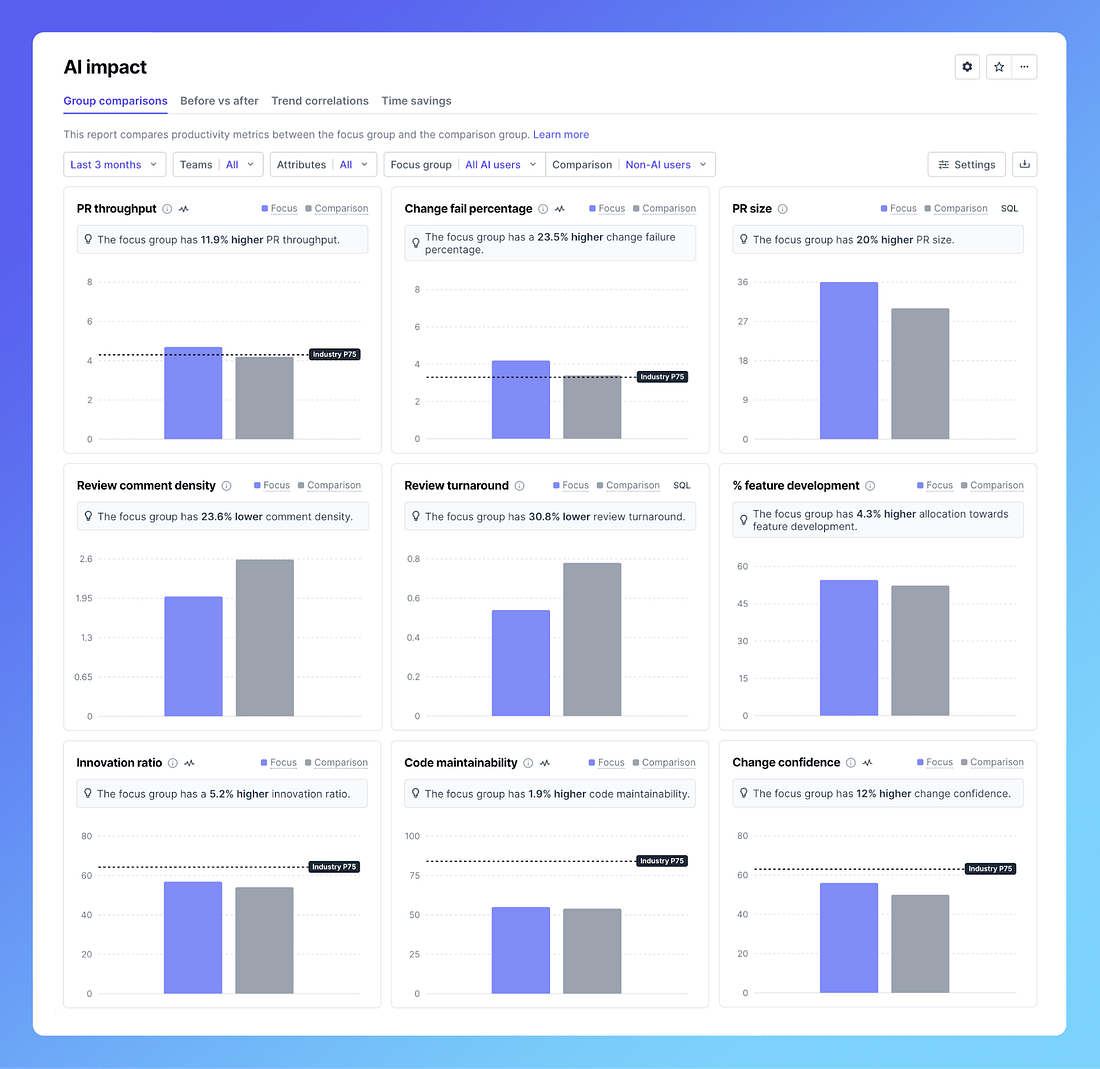

A 90% adoption rate only matters if it benefits the organization, teams, and individuals. For Dropbox, engineers who regularly use AI merge 20% more pull requests each week, while also reducing the change failure rate. Looking at all these metrics together helps them avoid over-indexing on a single thing like adoption, and missing the wider point. 3. Break down metrics by AI-usage levelIn order to better understand how AI is changing how developers get work done, Dropbox and other companies I interviewed do different kinds of analysis on their metrics, such as:

Many companies slice and dice their data to better observe patterns. This slicing and dicing is based on user attributes like role, tenure, region, and main programming language. It helps answer more detailed questions and to see important patterns, like junior engineers opening more PRs, and senior engineers slowing down because they spend more time reviewing those PRs. You can use such detailed research questions to find groups of developers who might need more training and enablement, or on the flip side, to find areas where AI is working really well and then devise a playbook for scaling those use cases. Using this style of comparison, Webflow was able to pinpoint groups for whom using AI tools saves the most time; in this case, it was devs who have been at the company more than 3 years. Webflow uses tools like Cursor and Augment Code, and similarly to Dropbox, has seen a boost of around 20% in PR throughput for AI users vs non-AI users. Start with solid baseline measurements if you want to do comparisons well. I mentioned earlier that companies which don’t yet have a solid footing in developer productivity will have a hard time measuring AI’s impact. I mean this theoretically and practically; first, they don’t know what signals to look for, and secondly, they don’t have good data for comparison. If you don’t yet have great baselines, now is the time to get them. To get started quickly using the Core 4 framework (which Dropbox, Adyen, Booking.com, and others use), here is a template and instructions on how to do so. You can also use system data and experience sampling data to complement periodic surveys like this, and we’ll cover how to use those techniques later. Taking these measurements once won’t give you much insight into AI impact; tracking them over time is what reveals trends and patterns. I cannot overstate how important an experimental mindset is for measuring the impact of AI. One common trait shared by the companies I interviewed for this article is that they use the data to answer questions and test predictions about how AI is impacting development. In many cases, they start with a concrete goal and work backwards; they don’t expect the data to magically reveal some truth about AI impact, or tell them what to do next. 4. Stay vigilant about maintainability, quality, and dev experienceOne thing that occasionally keeps me up at night is just how new AI-assisted development is. We don’t have years of longitudinal data that shows with confidence that there is no long-term risk to code maintainability or quality. And when I talk to executives and developers, a top concern of both is balancing short-term speed gains with longer-term tradeoffs like tech debt. Track metrics that keep each other in check. You’ll see that almost every single company is tracking Change Failure Rate alongside a measure of speed like PR throughput. These metrics can keep each other in check: for example, an increase in speed and a drop in quality may be a sign that something isn’t right. Beyond Change Failure Rate, there are other metrics I recommend tracking in order to keep a close eye on quality and maintainability. Some companies measure:

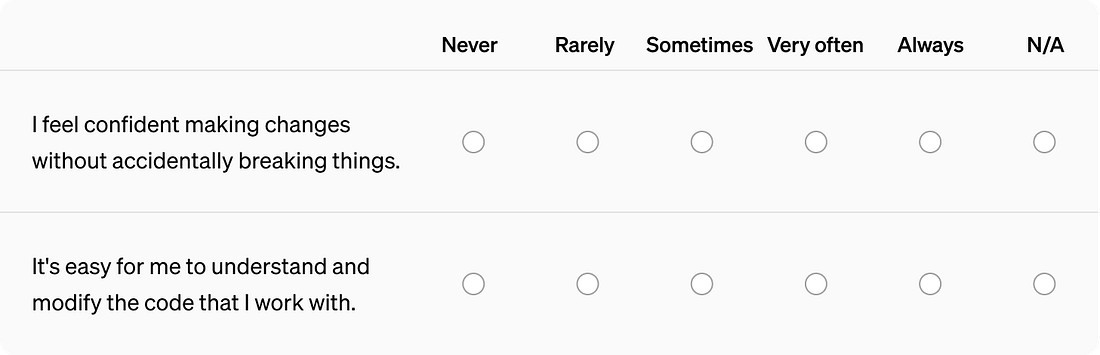

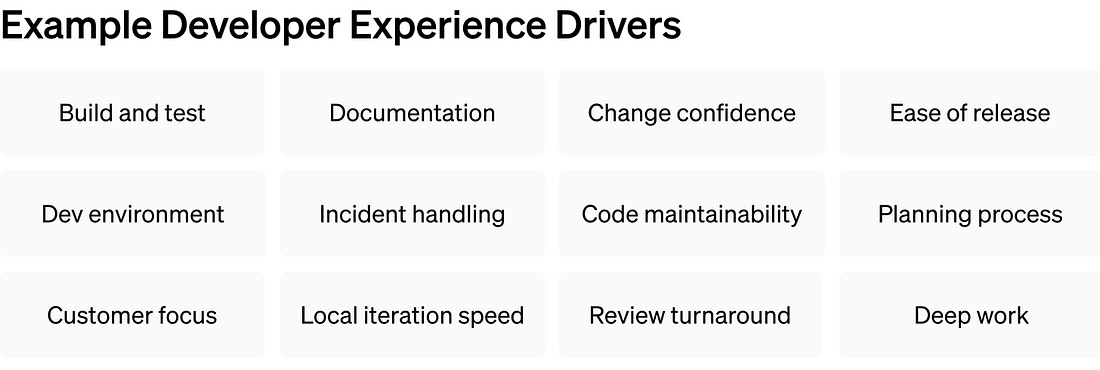

You need to collect system-metrics AND self-reported ones in order to get robust data, by which I mean data that covers dimensions of speed, quality, and maintainability. Some metrics, like PR throughput and deployment frequency, can be measured using system data from source control and build tooling, but metrics like “change confidence” and maintainability are critical to avoid longer-term negative impacts of AI. These can only be measured through self-reported data from developers themselves. If these topics don’t already come up in team discussions about AI, add them to the agenda. Even though this feedback is unstructured, it provides a richer understanding into existing concerns, and you can discuss proposed solutions and monitor progress over time. In order to correlate AI usage with changes in quality and maintainability over time you’ll want more structured data, and for this, a periodic developer experience survey is a good approach. Here’s two questions that help organizations understand change confidence and maintainability, specifically: Developer experience as a whole is another popular measurement to counterbalance speed and quality. It’s worth noting that developer experience has a slight marketing problem; it can easily come across as “ping-pong and beer”, instead of what it actually is: reducing friction and drag in the development process. DevEx includes all parts of the development lifecycle, from planning, building, and testing, release processes, all the way to production support. With AI tools, the risk is that we remove friction from some places like code authoring and testing, but then add friction in other places, like code reviews, incident handling, and maintainability.

Shelly Stuart, Director of Engineering at CircleCI, shares more about the importance of developer experience and developer satisfaction in the context of AI-assisted engineering:

If a tool has outstanding technical capabilities, it doesn’t matter if developers don’t actually like using it. Three-quarters of companies mentioned in this article also measure developer satisfaction or CSAT with AI tools, which is a good signal that the focus isn’t only on speed gains, but on building sustainable engineering practices that reduce friction in daily tasks. 5. Unique metrics, interesting trendsThere are interesting details hidden in all the metrics which caught my attention. While the industry has largely aligned on measuring time savings, quality, and speed, I find it interesting to look into outliers to learn about how different companies operate, and also to see what these metrics don’t show. Microsoft uses the concept of a “bad developer day” (BDD) to assess the impact of AI tools. It’s a real-time look into the toil and friction of devs’ day-to-day work, whereas developer experience surveys provide a lagging indicator. The idea is that AI should reduce the frequency and severity of BDDs. If so, Microsoft can determine whether AI is truly reducing friction, or is introducing new obstacles into the workflow. Several factors can turn a day from good to bad:

The company takes these factors and balances them against measurements of PR activity, which serve as a proxy for coding time. The reasoning is that a day might include some tasks that are toilsome or feel low value, but if the developer still gets some time to code and submit changes, this can tip the balance toward having a good day. Glassdoor measures experimentation as an outcome of AI tools. They track the number of A/B tests per month to understand whether AI tools are helping developers innovate faster. AI is an incredible tool for experimentation and prototyping, so it’s interesting to see an experimentation metric like this as a top-level AI impact metric. Relatedly, Glassdoor is doing nice work in turning power users into internal advocates for AI. They also use an uncommon measurement called “percentage capacity worked,” sometimes called “capacity utilization rate,” to measure each AI tool. This metric looks at the total potential capacity and actual utilization. This helps to reveal when a tool’s capabilities or adoption might be hitting a plateau, which is a sign to reallocate budget toward more capable alternatives. These days, acceptance rate is rarely measured. At one time, the percentage of AI coding suggestions being accepted was the leading AI metric. Now, we see it waning in popularity because of its narrow scope. This may be because acceptance rate focuses on the moment of suggestion, but misses a lot else, like:

Many companies don’t track the acceptance rate as a top-level metric anymore, but there are a few exceptions:

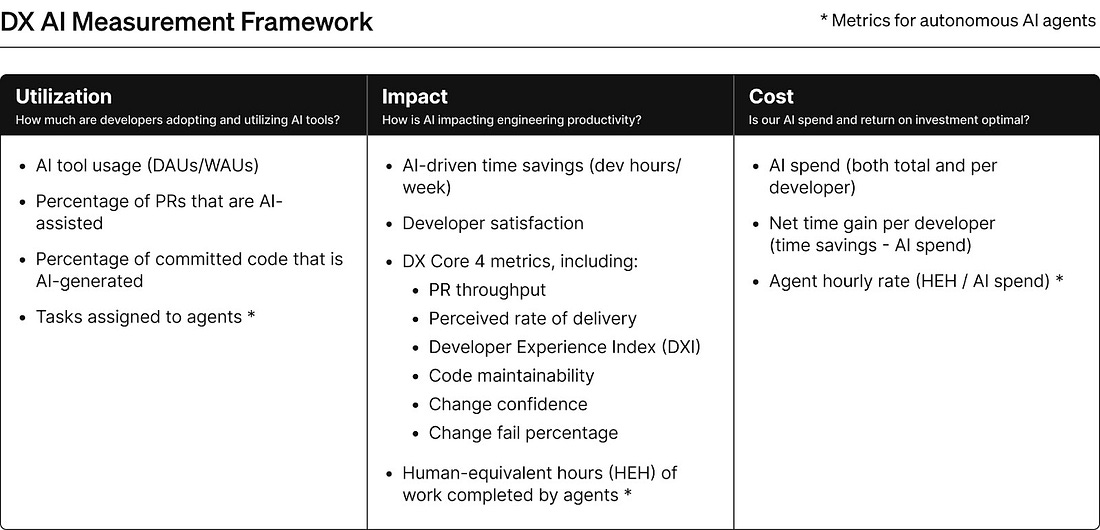

Spend and cost analysis isn’t widely measured, but this could change soon. Today, most organizations want to avoid discouraging developers from using AI by explicitly tracking spending. Some companies like Shopify have taken the opposite approach of introducing an AI Leaderboard to see which developers spend the most on token consumption, and then celebrate that experimentation. Still, companies need to ensure AI investments deliver a clear return on investment, and that the AI budget is worth it. ICONIQ’s 2025 State of AI report showed that internal AI productivity budgets are estimated to double this year compared to 2024. Most of this money is coming from R&D budgets, but some companies are reallocating headcount budgets to pay for AI tools that drive internal productivity. Basically, some companies plan to hire less in order to spend more on AI tools. We’re already seeing prices going up (no more $20-a-month!) and companies are trying to forecast their costs for the next year with token consumption and new tools coming on the market. All of this points to more price sensitivity, which means more scrutiny with measurement. Agent telemetry is not measured today – but this will likely change in the next 12 months. Agent-specific metrics are also largely missing, right now. At this stage, most teams aren’t yet breaking down AI impact to that level of granularity, and the telemetry data itself remains limited. Autonomous agentic workflows will continue to gain traction in the next 12-18 months. Indeed, this is one area of measurement that we expect to change to better reflect how companies use these tools in day-to-day work. Outside of coding-related activities, there’s little measurement happening. There’s not much direct measurement of AI tools beyond code authoring. It’s predicted that 2026 will be a big year for AI across the whole software development lifecycle (SDLC), and measurements will need to evolve to keep up. Use cases that are more concrete, such as code reviews and vulnerability scans will be better suited for telemetry, whereas ones whose output is more abstract are harder to measure because there’s not such a straight line between activity and impact. Even now, some companies limit their measurements to AI code assistants within the IDE or terminal, and don’t always count a planning session with ChatGPT, or using AI to sift through thousands of Jira tickets, as part of “AI-related time savings.” In the area of self-reported measurements of AI impact (e.g., “how much time did you save this week thanks to AI tools?”), I expect the surface area of measurement to expand to keep up with different types of tools. 6. How should you measure AI impact?What can you take away from all these metrics, and what should you implement in your own workplace? A few months ago, Abi Noda (co-author of the DevEx Framework) and I released the AI Measurement Framework. We worked directly with some of the companies I interviewed for this article in order to go deep into the measurement gaps they had. We had a front-row seat for decisions they needed to make with the data, and we were able to see firsthand what worked and what didn’t. We also collaborated with other researchers to include the past decade or more of developer productivity research into our recommendations. This framework is a blend of AI metrics and core metrics that show how and where AI is being used in your org, and most importantly, what the impact is on overall performance. Speed, quality, and maintainability are all represented, and we recommend keeping developer experience in the center. As with any framework, all of these measures need to be looked at together. No single metric in this framework is a good-enough measure by itself, especially the percentage of committed code that is AI-generated – however much it makes for a good headline. The framework covers what to measure, but we’re still left with how. To capture the many dimensions of AI impact, you need both qualitative and quantitative data. This is already well established when it comes to developer productivity, and the pattern also holds true for AI impact. Looking at the metrics from companies interviewed for this article, all mix system-level workflow metrics like PR throughput or DAU/WAU of AI tools, with self-reported data like the CSAT of AI tools, or time savings per week. Almost all companies mentioned in this article use DX to capture this data, although it’s possible to build custom systems for collecting and visualising it. There are a few ways to gather this data:

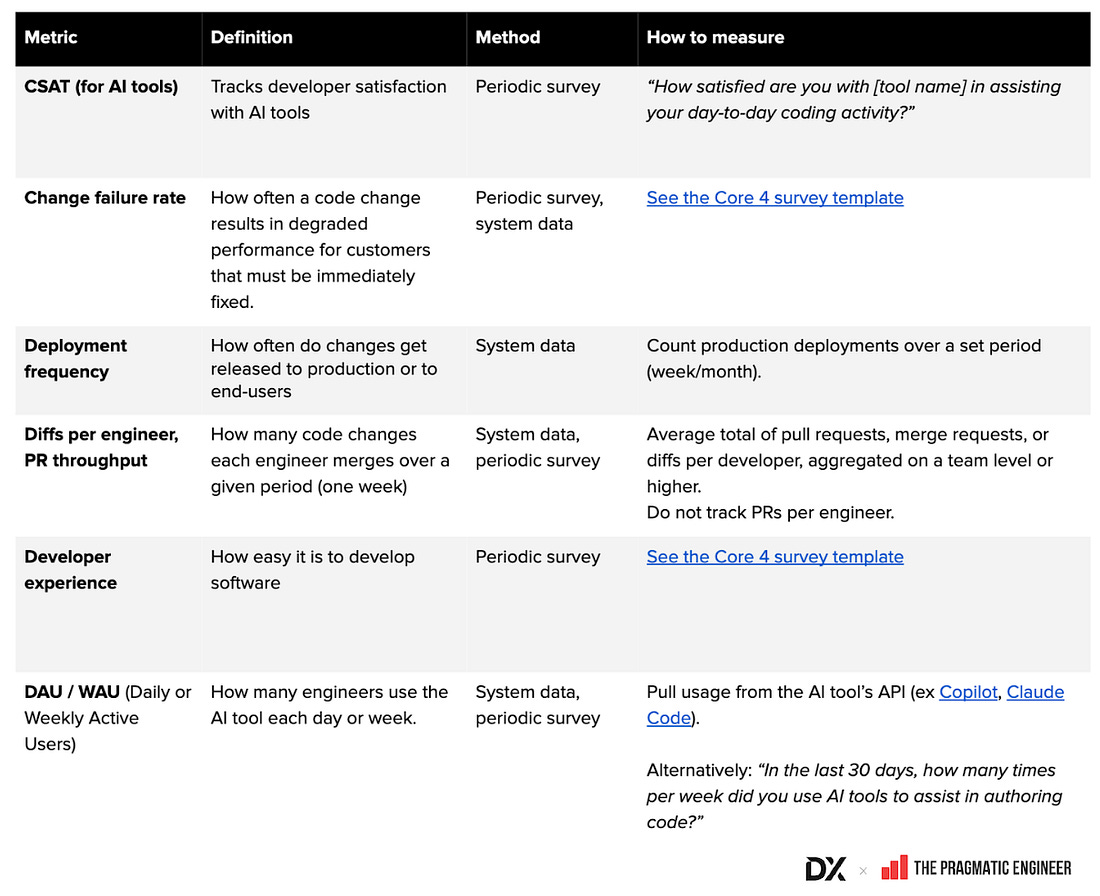

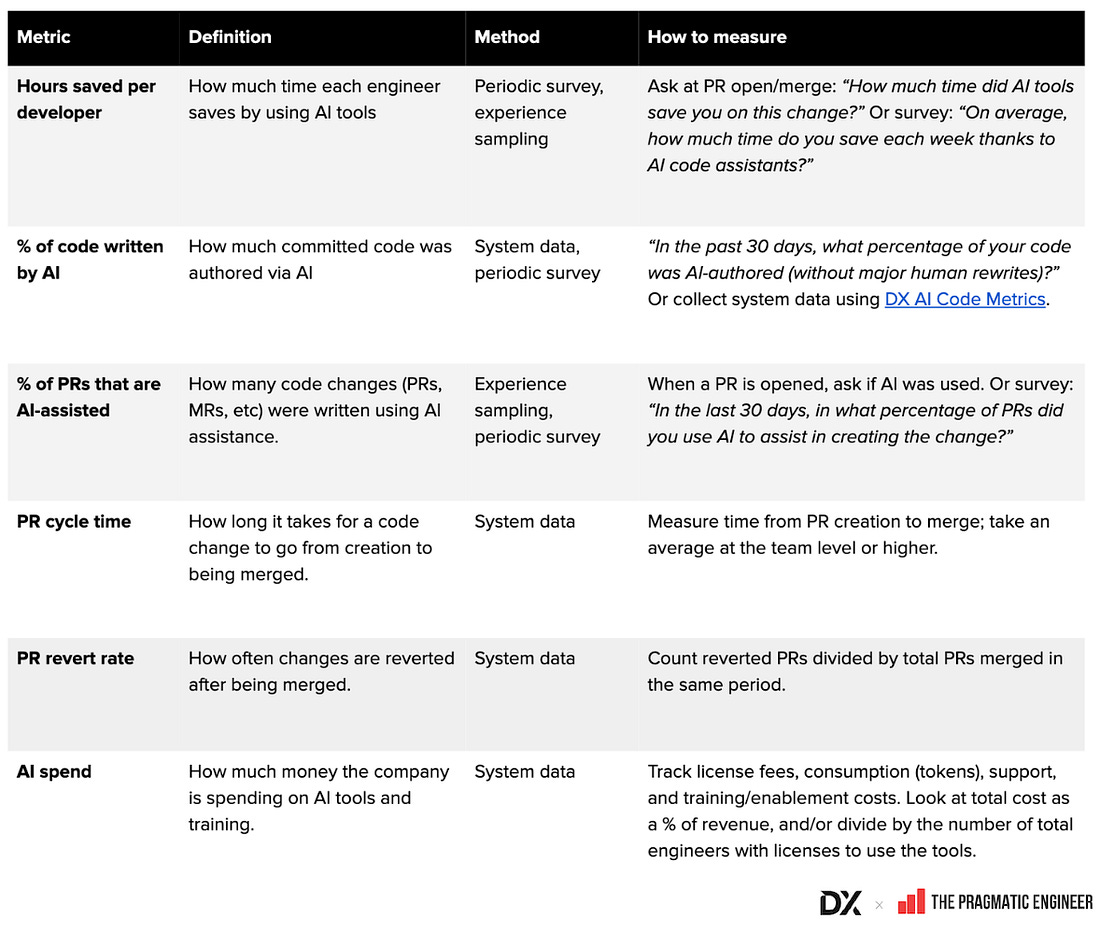

A periodic survey is the fastest way to get started, and will provide a mix of self-reported workflow data (PR throughput) as well as perceptive data that’s impossible to get from system data alone. You can deploy a survey and get access to data within a week or two, and the data collected is typically the right resolution for most decision-making. Remember, the more precise the measurement, the more expensive it is. When you’re hanging curtains, it’s okay to be off by a millimeter or so; not so much when you’re building a rocket. Most decisions we make as engineering leaders are curtain-hanging decisions, not rocket-building decisions, and we need enough precision to go in the right direction. Over time, you can introduce other types of data. Layering data collection methods allows you to cross-validate findings from multiple data sources. For example, ask for developers’ perception of quality practices while also tracking change failure rate and the number of incidents. Definitions and calculation methods for common AI metrics. As you take these concepts and apply them to your own teams, use this glossary (a Google Sheet) of common AI metrics to figure out how to define and collect the data. You can find a full glossary of AI metrics and developer productivity metrics below: How to bring these ideas in-houseThe companies I interviewed for this article don’t have all the answers on AI strategy, but they have enough visibility into what’s happening that they can tell soon enough if something isn’t working. Remember, we’re not just chasing adoption here, or any single metric. We’re trying to see if AI is helping our organization get better at delivering high-quality software at speeds that solves customer problems. We use metrics to understand how, where, and why AI is achieving those outcomes or not, so that we can double down or change our approach. Think about your own AI measurement strategy. Can you answer this question:

If the answer is “not yet”, here are some discussion points to take to your next leadership meeting.

7. How Monzo measures AI impactGergely here, again. Thanks very much to Laura for collecting all these details from no less than 18 companies. To close this deepdive with something more specific, Laura and I did an interview with the team at Monzo Bank, to understand their journey into learning how well AI tools work for their software engineers. Monzo is good for this because it has a strong engineering culture, and people there keep their feet on the ground by not buying into AI hype. Suhail Patel leads the platform teams at Monzo Bank, which is an innovative neobank. We asked how the team figures out how well their AI tools work. My questions are in italic, with Suhail’s answers in quotes. What were the first AI tools you introduced at Monzo?

What’s your advice for engineering leads about evaluating AI tools?

How can you tell if AI tools actually work and are worth the money?

Why is it so hard to measure how well these AI tools work, and what are you measuring?

Which areas do these tools work really well in?

What is something counterintuitive that you’ve learned about AI dev tools?

Which areas have you decided to NOT use AI tools in, at all?

What’s your overall thinking about AI coding tools and software engineering?

TakeawaysMany thanks to Laura for her research and getting data on how the companies in this article measure AI efficiency, and also to Suhail for sitting down to talk through what they see on the ground at Monzo. Measuring the impact of AI is very new, and there is no one “best practice” for it. Companies that are similar enough in size and operate in similar markets like Microsoft and Google, measure different things around AI. The tables above showing what the companies measure illustrate that each place has a different “flavor” when it comes to measuring AI efficiency. Measuring conflicting metrics is common – almost all companies do it. The most common example is measuring change failure rate (or similar metrics like frequency/percentage of bugs shipped), while also measuring pull request frequency. The first metric is about reliability, and the next is about speed. Shipping faster only makes sense when it doesn’t result in an impact on reliability; so you want to measure both! Measuring the impact of AI tools on engineering teams is a similarly hard problem to measuring developer productivity. Accurately measuring developer productivity is tricky and the industry has struggled with it for well over a decade. We know that there is no one single metric that can tell us how productive an engineering team is because teams can simply optimize for any one metric while not actually being more productive. In 2023, consultancy giant McKinsey confidently declared that they’d “cracked” how to measure developer productivity. But the creator of the extreme programming methodology, Kent Beck, and I, were skeptical of this claim, and we published a counterpoint in the article Measuring developer productivity? A response to McKinsey. Until we figure out how to measure developer productivity, I don’t think we’ll fully crack how to measure the impact of AI tools on developer productivity. Still, while there’s no grand solution, we should still experiment with how to better answer the question: “how are all these AI coding tools changing the daily and monthly efficiency of individuals, teams, and companies?” You’re on the free list for The Pragmatic Engineer. For the full experience, become a paying subscriber. Many readers expense this newsletter within their company’s training/learning/development budget. If you have such a budget, here’s an email you could send to your manager. This post is public, so feel free to share and forward it. If you enjoyed this post, you might enjoy my book, The Software Engineer's Guidebook. Here is what Tanya Reilly, senior principal engineer and author of The Staff Engineer's Path said about it:

|

Comments

Post a Comment