Inside Google's Engineering Culture: Part 1

👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a subscriber-only issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. If you’ve been forwarded this email, you can subscribe here. Inside Google's Engineering Culture: Part 1A broad and deep dive in how Google works, from the perspective of SWEs and eng managers. What makes Google special from an engineering point of view, engineering roles, compensation, and moreToday, the tech giant Google reaches more people with its products than any other business in the world across all industries, via the likes of Google Search, Android, Chrome, Gmail, and more. It also operates the world’s most-visited website, and the second most-visited one, too: YouTube. Founded in 1998, Google generated the single largest profit ($115B after all costs and taxes) of all companies globally, last year. Aside from its size, Google is known for its engineering-first culture, and for having a high recruitment bar for software engineers who, in return, get a lot of autonomy and enjoy good terms and conditions. Employees are known as “Googlers,” and new joiners – “Nooglers” – get fun swag when they start. An atmosphere of playful intellectual curiosity is encouraged in the workplace, referred to internally as “Googleyness” – more on which, later. This culture is a major differentiator from other Big Tech workplaces. But what is it really like to work at Google? What’s the culture like, how are things organized, how do teams get things done – and how different is Google from any other massive tech business, truly? This article is a “things I wish I’d known about Google before joining as an SWE / engineering manager”. It’s for anyone who wants to work at Google, and is also a way to learn, understand, and perhaps get inspired by approaches that work for one of the world’s leading companies. This mini-series of articles focusing on Google contains more information about more aspects of its engineering culture than has been published in one place before, I believe. We’ve spent close to 12 months researching it, including having conversations with 25 current and former engineering leaders and software engineers at Google; the majority of whom are at Staff (L6) level or above. Of course, it’s impossible to capture every detail of a place with more than 60,000 software engineers, and whose product areas (Google’s version of orgs) and teams work in different ways. Google gives a lot of freedom to engineers and teams to decide how they operate, and while we cannot cover all that variety, we aim to provide a practical, helpful overview. In part 1 of this mini-series, we cover:

This article is around twice as long as most deepdives; there are just so many details worth sharing about Google! For similar deepdives, see Inside Meta’s engineering culture, Inside Amazon’s engineering culture, and other engineering culture deepdives — including that of OpenAI, Stripe and Figma. Programming note: this week, an episode of The Pragmatic Engineer Podcast will be released tomorrow (Wednesday), and there will be no edition of The Pulse. 1. OverviewLet’s begin with a quick rundown of the numbers that give Google the most users and customers of any business, globally:

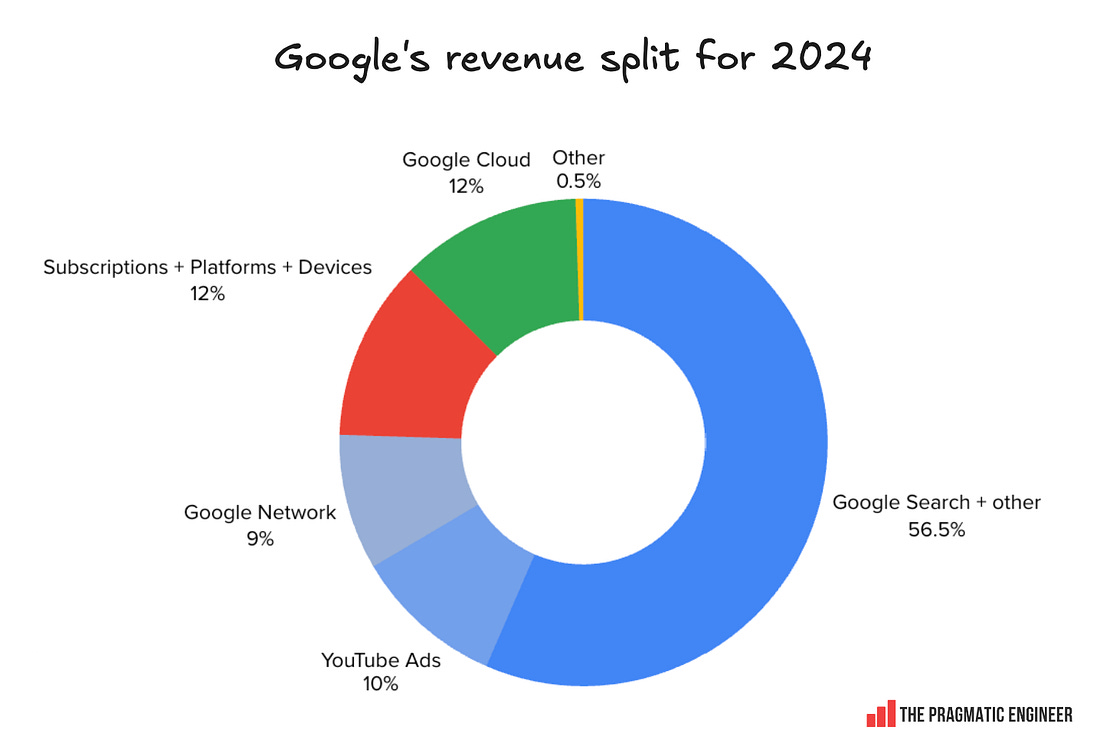

In 2015 when Google renamed itself “Alphabet”, the motivation was to separate the core web search business that earned the lion’s share of revenue from loss-making, “moonshot” ventures like Waymo, Google DeepMind, Google Fiber, etc. In practice, almost all revenue generated by Alphabet comes from the Google organizational unit, and not much has changed since. This article uses the name “Google” when referencing Alphabet. Incredibly profitable & ads-heavyIn absolute terms, Google is currently the most profitable company in the world; it generated $115 billion in profit (net income) over the past 12 months on $371 billion in revenue. For comparison, here are other Big Tech companies’ net incomes during the period:

At its core, Google is still an advertising company; around 75% of revenue comes from selling ads on Google Search, YouTube, and the Google Ads network. However, the business has several services that don’t rely on ads for revenue:

Google has several loss-making businesses that might one day turn a profit, such as:

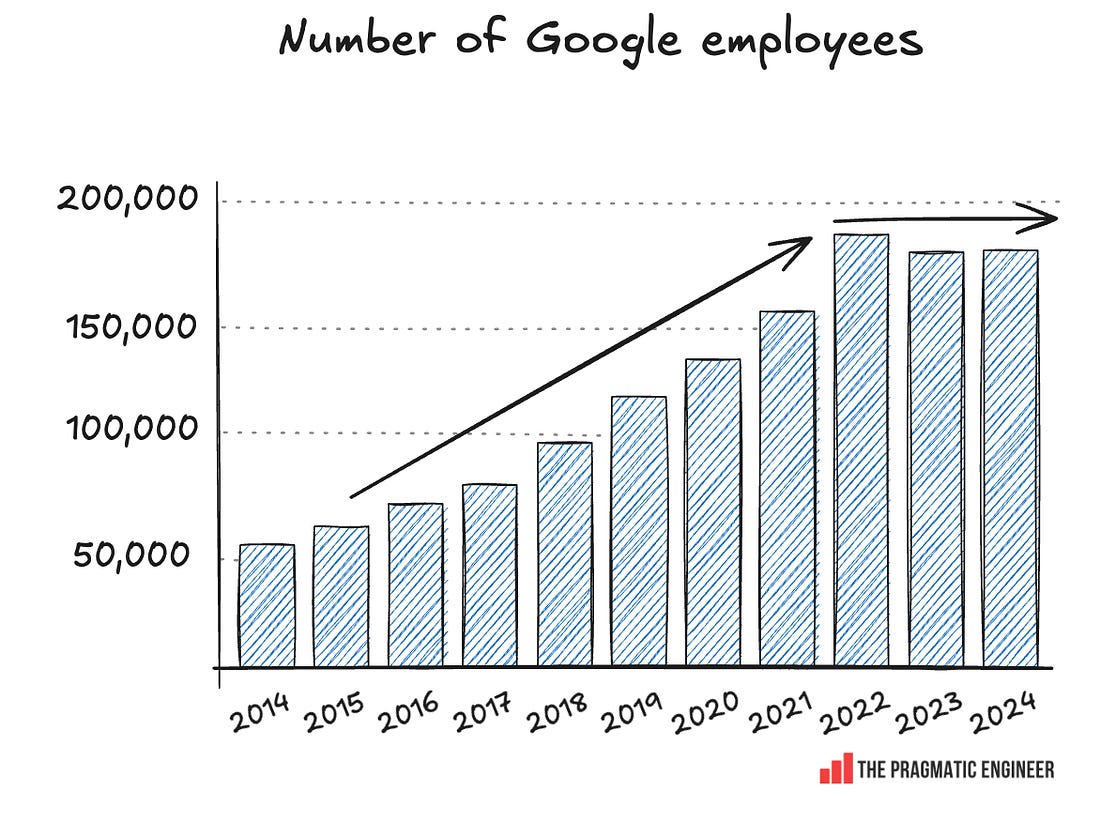

Global officesGoogle employs 183,000 people worldwide and hit peak headcount in 2022, with 190,000 workers. In 2023, there were mass layoffs and headcount has since stopped rising: As mentioned above, Google employs around 60,000 software engineers, which we can deduce because in 2020 this number was 50,000, as shared in the book “Software Engineering at Google,” – around 35% of all staff. Headcount growth since that time suggests that 60K engineers work there today. This makes Google one of the largest employers of software engineers; Amazon employs nearly 35,000 developers, and Meta around 32,000 software engineers. We’re confident Google has the highest “software engineering ratio” among the Big Tech giants. Google runs more than 25 engineering offices. The biggest:

Google has more than 70 offices across 50+ countries. The total number of offices is higher than engineering offices, because many of Google’s offices have no software engineering teams in those locations, but are for non-technical teams like Sales, Marketing, Consulting (e.g. for Google Cloud), and other functions. Although not typical, Google can hire engineers to work from mainly non-engineering offices as “singletons”. A current Google engineer told us:

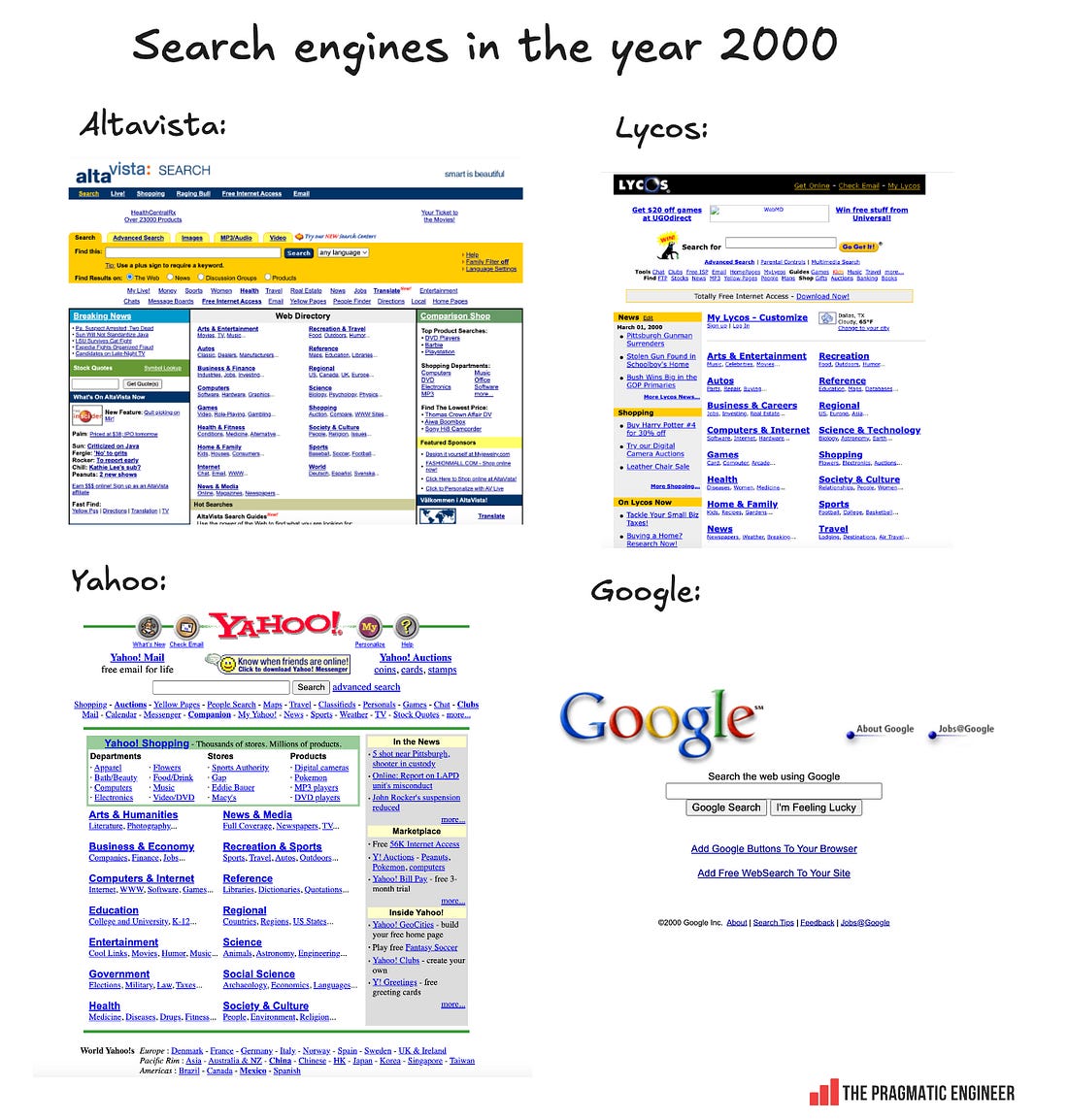

“Singletons” can also work in engineering offices: in that case, they would be the lone engineer working for their team in that location, everyone else on their team being in other locations. Singletons are not common at Google, but our research suggests there are many more of them than at other Big Tech companies and larger scaleups. History, mission, valuesAs is well known by now, Google was founded by PhD students Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who devised a more efficient search engine algorithm called PageRank. Using PageRank for searching the web resulted in much-improved results than the most popular rival search engines of the time, such as Yahoo!, AltaVista, Lycos, and Ask Jeeves. Some of these were portals which “featured” sites to visit (like AltaVista), and others were rudimentary search engines that gave up to 15 not-particularly-accurate results. The rest, as they say, is history: two years after launching, Google became the dominant search engine and also a verb (“let me Google this.”) It gave more and better search results, and had a much cleaner interface than its rivals. The company’s mission has changed over time:

Google also has five core values:

Current Googlers report that these values are not particularly emphasized during day-to-day work, and that they feel pretty abstract and “corporate”. This light-touch approach is different from competitors like online retailer Amazon, whose 16 leadership principles might as well be chiselled in stone on the walls. “Googleyness” is something most workers at the company share. It’s a trait Google focuses on during its hiring process as something all employees should possess. The term is vague, but adds up to being smart, adaptable, and a team player who’s nice to be around. We cover Googleyness more in the “Hiring” section.

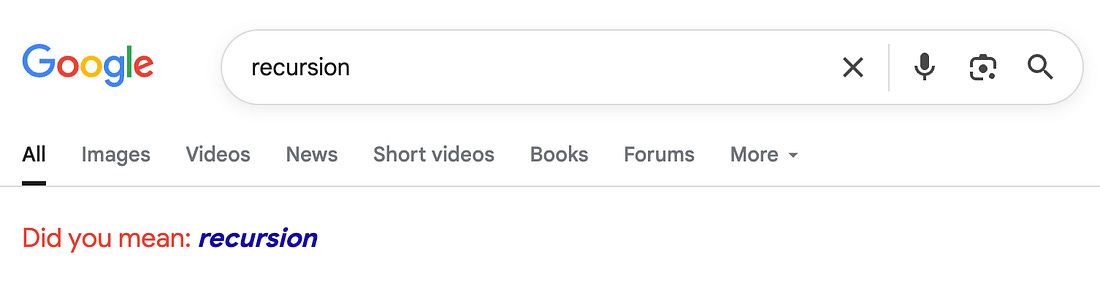

There are plenty of publicly observable instances of “Googleyness” in Google’s own products, which show just how engineering-driven its culture is. For example, try searching “recursion” on Google: 2. What makes Google special?From talking with 25 current and former Googlers, here’s what makes it distinct from other Big Tech companies. No “single” GoogleGoogle is divided into Product Areas which operate like standalone companies. These are often called “PAs” or “orgs” internally. The main PAs:

Orgs have their own goals, priorities, metrics, and planning cadences. And within each org, teams have a lot of independence to decide their way of working. An engineer’s experience in one team in an org can be very different from another engineer’s in a different team in another org! Here’s how one current Google engineer explained it to us:

A tech lead confirmed that priorities differ by PA:

One engineering cultureEven though product areas and teams work independently, the engineering culture seems pretty universal, judging by the engineers we’ve talked to. Practices, tooling, and tech stacks are very similar. Whether someone works in YouTube, Ads and Commerce, or another product area, they use the same internal tools, the same processes for things like code review, testing, and documentation, and also the same monorepo and continuous integration processes – except for a few open source projects like Android and Chromium. That most of Google’s 60,000 engineers use almost identical tooling means it is little effort to move teams, which helps make internal moves easy, as it involves a lot less change to processes and tooling, meaning a lower cognitive load that makes onboarding faster, overall. Politics and culture vary between PAs and teams. It would be impossible for the culture to be identical in thousands of engineering teams, split across dozens of locations. Here are the big differences, according to engineers:

Unique engineering stackGoogle’s engineering org exists in a different world from that which other tech companies operate in. This comes down to one thing: scale. Google had to build systems at the scale of serving hundreds of millions of users a decade before any other company in the world reached a similar scale. This meant it innovated unique systems and solutions to massive scaling challenges, and that publicly-available tools were shipped outside Google only a decade or so later. Whatever tools or vendors your current company uses to deal with scale, it’s likely that Google built its own versions 10 or more years earlier:

Google occupies an unusual position where it makes no sense to adopt industry-standard tools like GitHub and Kubernetes because its existing stack is so well integrated. A current Google engineer explained why it rarely uses external services or tools, even if they can handle Google’s scale:

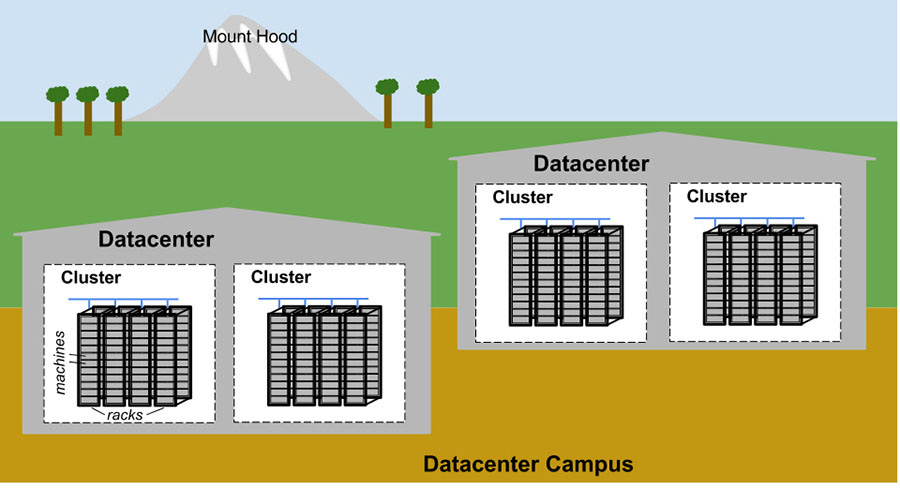

Building systems differently since day oneEngineering at Google has been different from the rest of the world since it was founded. From its beginnings in 1998, the company bet big on speed and reliability being differentiators for all its products. They expected the web search tool to deal with planet-scale load, and the same for subsequent products like Gmail that launched with 1GB of free storage in 2004. This was unheard of at a time when storage was much more expensive. The assumption was that these products needed to be able to handle billions of users. To achieve this scale, Google simply had to build a custom tech stack from the start, as there were no commercially-available tech stacks around to handle planet-scale load. Back in the late ‘90s, the conventional wisdom was to vertically scale machines; that is, buy the biggest possible server (called a mainframe), and try to make an application run on a single server. Sun was one of the biggest mainframe vendors of the time, and most companies invested heavily in expensive, high-performance hardware. Google took a different route by choosing to buy cheap, commodity hardware, and to build data center clusters that made use of tens of thousands of relatively cheap machines to handle loads that not even the largest mainframes in the world could soak up. Here’s how Google’s search cluster worked in 2003, from the Google whitepaper describing the Google cluster architecture:

Back then, this kind of approach was revolutionary, and no other company published so much detail about its custom data center setup. Google kept publishing details on how it organized and operated clusters, such as this writeup in the “Site Reliability Engineering at Google” book: “The topology of a Google data center:

Unusual opennessCompared to every other Big Tech company, Google has been very open and transparent about how it works externally and internally. Note, this openness seems to have reduced since around 2020. Internally, basically everything used to be available to all workers: planning docs, strategies, code, documentation, et-al. This company-wide access changed to Product Area-wide access following leaks in 2020. A former Google Cloud engineer told us:

Externally, Google has published more than 10,000 papers with details about how the company works and how products are built. No other business has published more about its inner workings. Famously, in 2017 Google published a paper titled Attention is All You Need, describing a novel network architecture called “transformers.” This paper was the foundation for Large Language Models (LLMs) and this idea is at the core of ChatGPT and other LLMs. By publishing this paper instead of holding on to its breakthrough, Google may have brought forward the AI boom by a few years! Tech islandEverything about software engineering is unique at Google. New joiners can throw out their knowledge of how to use source control, how to run CI/CD, and how to manage infrastructure. Google has different, unique systems for everything related to building, deploying, and maintaining software, and all of it has to be learnt. The term “tech island” was coined by Urs Hölzle, Google employee #8, in an internal document nearly a decade ago. As a former Googler told us:

The debate on whether Google should continue as a tech island or get closer to the mainland is controversial, a current engineer at Google told us:

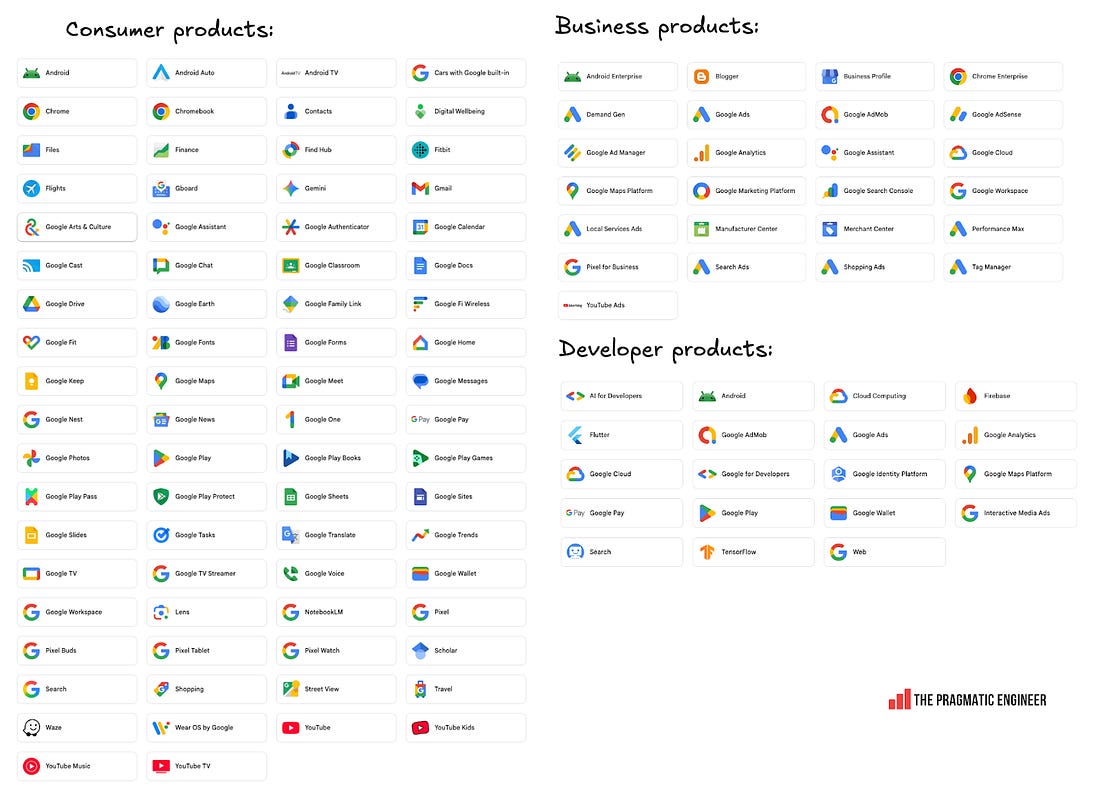

Doing many thingsCompared to the likes of Meta and Amazon, Google builds a plethora of products, platforms, and technologies:

The Big Tech company closest to Google in sheer breadth of products is probably Microsoft. The Windows maker also has a search engine (Bing), operating system (Windows), browser (Edge), hardware (Surface), cloud provider (Azure), enterprise tools (Office 365, Microsoft Teams), social networks (LinkedIn, GitHub), developer tools (VS Code), and programming languages / open source (TypeScript, .NET and others). Being an engineer at Google means potentially working with anything from docs, to video transcoding, to mobile apps, or infrastructure. If a new challenge is sought, workers can switch teams to a completely different area: 3. Levels and rolesGoogle has a dual-track career ladder for software engineers and engineering managers – plus an interesting role called Tech Lead Manager (TLM). Each level typically pays very similarly in total compensation (we cover more on compensation in the next section). This means that as an individual contributor, it’s possible to earn similarly to managers and directors without needing to manage engineers. At L5 and L6, engineers who take on tech lead responsibilities often have the opportunity to join the manager career ladder. Those who want to lead small teams but not become managers can be TLMs. Here’s how levels look on these parallel tracks:... Subscribe to The Pragmatic Engineer to unlock the rest.Become a paying subscriber of The Pragmatic Engineer to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content. A subscription gets you:

|

Comments

Post a Comment