Inside Google’s Engineering Culture: the Tech Stack (Part 2)

👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a subscriber-only issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. If you’ve been forwarded this email, you can subscribe here. Inside Google’s Engineering Culture: the Tech Stack (Part 2)Deepdive into how Google works from SWEs’ perspectives at the Tech Giant: planet-scale infra, tech stack, internal tools, and more“What’s it really like, working at Google?” is the question this mini series looks into. To get the details, we’ve talked with 25 current and former software engineers and engineering leaders between levels 4 and 8. We also spent the past year researching: crawling through papers and books discussing these systems. The process amassed a wealth of information and anecdotes that are combined in this article (and mini-series). We hope it adds up to an unmatched trove of detail compared to what’s currently available online. In Part 1, we covered Google’s engineering and manager levels, compensation philosophy, hiring processes, and touched on what makes the company special. Today, we dig into the tech stack because one element that undoubtedly makes the company stand out in the industry is that Google is a tech island with its own custom engineering stack. We cover:

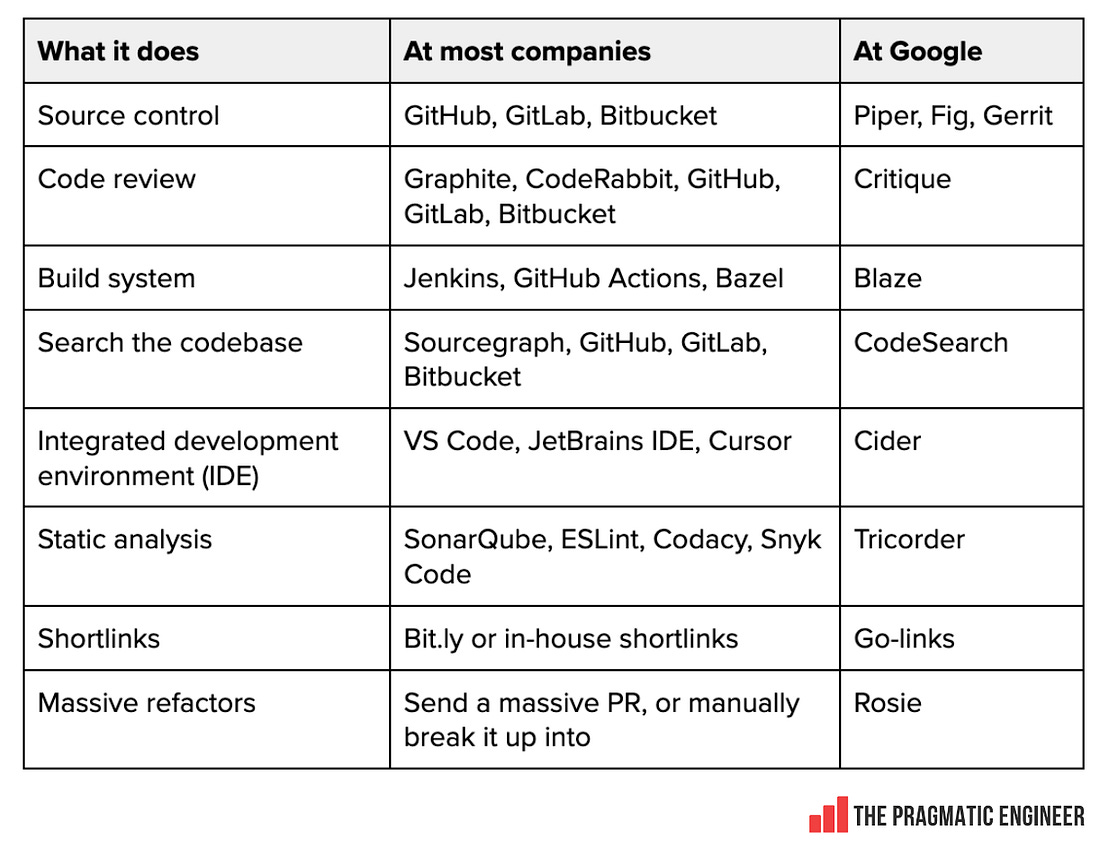

The bottom of this article could be cut off in some email clients. Read the full article uninterrupted, online. 1. Planet-scale infraGoogle’s infrastructure is distinct from every other tech company because it’s all completely custom: not just the infra, but also the dev tools. Google is a tech island, and engineers joining the tech giant can forget about tools they’re used to – GitHub, VS Code, Kubernetes, etc. Instead, it’s necessary to use Google’s own version of the tool when there’s an equivalent one. Planet-scale vs GCPInternally, Google engineers say “planet scale” as the company’s capacity to serve every human on Earth. All its tooling operates at global scale. That’s in stark contrast to Google Cloud Platform (GCP), with no such “planet-scale” deployment options built in – it’s possible to build applications that can scale that big, but it would be a lot of extra work. Large GCP customers which managed to scale GCP infrastructure to planetary proportions include Snap, which uses GCP and AWS as their cloud backend, and Uber that uses GCP and Oracle, as detailed in Inside Uber’s move to the cloud. Google doesn’t only run the “big stuff” like Search and YouTube on planet-scale infrastructure; lots of greenfield projects are built and deployed on this stack, called PROD. As an aside, the roots of database Planetscale (the database Cursor currently runs on) run to Google, and its “planet-scale” systems. Before co-founding Planetscale, Sugu Sougoumarane worked at Google on YouTube, where he created Vitess, an open source database to scale MySQL. Sugu now works on Multigres, an adaptation of Vitess for Postgres. I asked where the name Planetscale comes from. He said:

Planetscale originally launched with a cloud-hosted instance of Vitess and gained popularity thanks to its ability to support large-scale databases. It’s interesting to see Google’s ‘planet-scale’ ambition injected into a database startup, co-founded by a Google alumnus! PROD stack“PROD” is the name for Google’s internal tech stack, and by default, everything is built on PROD: both greenfield and existing projects. There are a few exceptions for things built on GCP; but being on PROD is the norm. Some Googlers say PROD should not be the default, according to a current Staff software engineer. They told us:

Building on GCP can be painful for internal-facing products. A software engineer gave us an example:

It makes no sense to use a public GCP service when there’s one already on PROD. Another Google engineer told us the internal version of Spanner (a distributed database) is much easier to set up and monitor. The internal tool to manage Spanner is called Spanbob, and there’s also an internal, enhanced version of SpanQSL. Google released Spanner on GCP as a public-facing service. But if any internal Google team used the GCP Spanner, they could not use Spanbob – and have to do a lot more work just to set up the service! – and could not use the internal, enhanced SpannerSQL. So, it’s understandable that virtually all Google teams choose tools from the PROD stack, not the GCP one. The only Big Tech not using its own cloud for new productsGoogle is in a position where none of its “core” products run GCP infrastructure: not Search, not YouTube, not Gmail, not Google Docs, nor Google Calendar. New projects are built on PROD by default, not GCP. Contrast this with Amazon and Microsoft, which do the opposite:

Why do Google’s engineering teams resist GCP?

A current Google software engineer summed it up:

Another software engineer at the company said:

The absence of a top-down mandate is likely another reason. Moving over from your own infra to use the company’s cloud is hard! When I worked at Skype as part of Microsoft in 2012, we were given a top-down directive to move Skype fully over to Azure. The Skype Data team did that work, who were next to me, and it was a grueling, difficult process because Azure just didn’t have good-enough support or reliability at the time. But as it was a top-down order, it eventually happened anyway! The Azure team prioritized the needs of Skype and made necessary improvements, and the Skype team made compromises. Without pressure from above, the move would have never happened, since Skype had a laundry list of reasons why Azure was suboptimal as infrastructure, compared to the status quo. Google truly is a unique company with internal infrastructure that engineers consider much better than its public cloud, GCP. Perhaps this approach also explains why GCP is the #3 cloud provider, and doesn’t show many signs of catching AWS and Azure. After all, Google is not giving its own cloud the vote of confidence – never mind a top-down adoption mandate! – as Amazon and Microsoft did with theirs. 2. MonorepoGoogle stores all code in one repository called the monorepo – also referred to as “Google3”. The size of the repo is staggering – here are stats from 2016:

Today, the scale of Google’s monorepo has surely increased several times over. The monorepo stores most source code. Notable exceptions are open-sourced projects:

As a fun fact, these open source projects were hosted for a long time on an internal Git host called “git-on-borg“ for easy internal access (we’ll cover more on Borg in the Compute and Storage section.) This internal repo was then mirrored externally. Trunk-based development is the norm. All engineers work in the same main branch, and this branch is the source of truth (the “trunk”). Devs create short-lived branches to make a change, then merge back to trunk. Google’s engineering team has found that the practice of having long-lived development branches harms engineering productivity. The book Software Engineering at Google explains:

In 2016, Google already had more than 1,000 engineering teams working in the monorepo, and only a handful used long-lived development branches. In all cases, using a long-lived branch boiled down to having unusual requirements, with supporting multiple API versions a common reason. Google’s trunk-based development approach is interesting because it is probably the single largest engineering organization in the world, and it’s important that it has large platform teams to support monorepo tooling and build systems to allow trunk-based development. In the outside world, trunk-based development has become the norm across most startups and scaleups: tools that support stacked diffs are a big help. Documentation often lives in the monorepo and this can create problems. All public documentation for APIs on Android and Google Cloud are checked into the monorepo, which means documentation files are subject to the same readability rules as Google code. Google has strict readability constraints on all source code files (covered below). However, with external code, the samples don’t usually follow the internal readability guidelines by design! For this reason, it has become best practice to have code samples outside of the monorepo, in a separate GitHub repository, in order to avoid the readability review (like naming an example file quickstart.java.txt). For example, here’s an older documentation example where the source code is in a separate GitHub repository file to avoid Google’s readability review. For newer examples like this one, code is written directly into the documentation file which is set up to not trigger a readability review. Not all of the monorepo is accessible to every engineer. The majority of the codebase is, but some parts are restricted:

Architecture and systems designIn 2016, Google engineering manager Rachel Potvin explained that despite the monorepo, Google’s codebase was not monolithic. We asked current engineers there if this is still true, and were told there’s been no change:

Another Big Tech that has been using a monorepo since day one is Meta. We covered more on its monorepo in Inside Meta’s engineering culture. Each team at Google chooses its own approach to system design, which means products are often differently designed! Similarities lie in the infra and dev tooling all systems use, and low-level components like using Protobuf and Stubby, the internal gRPC. Below are a few common themes from talking with 20+ Googlers:

A current Google engineer summarized the place from an architectural perspective:

This metaphor derives from the book The Cathedral and the Bazaar, where the cathedral refers to closed-source development (organized, top-down), and the Bazaar is open-source development (less organized, bottom-up.) A few interesting details about large Google services:

3. Tech stackOfficially-supported programming languagesInternally, Google officially supports the programming languages below – meaning there are dedicated tooling and platform teams for them:

Engineers can use other languages, but they just won’t have dedicated support from developer platform teams. TypeScript is replacing JavaScript in Google, several engineers told us. The company no longer allows new JavaScript files to be added, but existing ones can be modified. Kotlin is becoming very popular, not just on mobile, but on the backend. New services are written almost exclusively using Kotlin or Go, and Java feels “deprecated”. The push towards Kotlin from Java is driven by software engineers, most of whom find Kotlin more pleasant to work with. For mobile, these languages are used:

Language style guides are a thing at Google and each language has its own style guides. Some examples:

Interoperability and remote procedure callsProtobuf is Google’s approach to interoperability, which is about working across programming languages. Protobuf is short for “Protocol buffers”: a language-neutral way to serialize structured data. Here’s an example protobuf definition:

This can be used to pass the Person object across different programming languages; for example, between a Kotlin app and a C++ one. An interesting detail about Google’s own APIs, whether it’s GRPC, Stubby, REST, etc, is that they are all defined using protobuf. This definition then generates API clients for all languages. And so internally, it’s easy to use these clients and call the API without worrying about underlying protocol. gRPC is a modern, open source, high-performance remote procedural call (RPC) framework to communicate between services. Google open sourced and popularized this communication protocol, which is now a popular alternative to REST. The biggest difference between REST and gRPC is that REST uses HTTP for human-readable formatting, while gRPC is a binary format and outperforms REST with smaller payloads and less serialization and deserialization overhead. Internally, Google services tend to communicate using the “Google internal gRPC implementation” called Stubby, and to not use REST. Stubby is the internal version of gRPC and the precursor to it. Almost all service-to-service communication is via Stubby. In fact, each Google service has a Stubby API to access it. gRPC is only used for external-facing comms, such as making external gRPC calls. The name “stubby” comes from how protobuffers can have service definition, and that stubs can be generated from those functions from each language. And from “stub” comes “stubby.” 4. Dev toolingIn some ways, Google’s day-to-day tooling for developers most clearly illustrates how different the place is from other businesses: Let’s go through these tools and how they work at the tech giant:... Subscribe to The Pragmatic Engineer to unlock the rest.Become a paying subscriber of The Pragmatic Engineer to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content. A subscription gets you:

|

Comments

Post a Comment